10th December – Human Rights Day

1 Joseph De Piro’s justice

Joseph De Piro’s leading virtue was undoubtedly his charity. But a central dimension of this virtue was certainly his justice.

1.1 Justice with the employees depending on him

1.1.1 The employees at the Major Seminary, Mdina, Malta

It seemed that the rectors of the Maltese Major Seminary had the duty to present to the Archbishop of Malta a yearly report about the different aspects of the life of the Seminary. The Servant of God presented the one for the scholastic year 1919-20 on 27th August 1920. Having analysed the academic aspect, Rector De Piro presented the servants’ situation, “12. All through the year the servants’ contribution has been quite satisfactory. We therefore ask your Excellency to revise their salaries, which is certainly not enough for today’s needs.”

1.1.2 The employees at St Joseph’s Orphanage, Malta

At the time of De Piro there were two groups of workers at St Joseph’s, Malta: the house attendants and the workshop instructors. The former group was made up of the cook, the porter, the bandmaster, the wardrobe master, and a certain Zaru. The printing composer, the printer, the carpenter, the shoemaker, the bookbinder, the tailor, the assistant carpenter and the son of the shoemaker worked in the workshops. In all there were thirteen employees. George Wilson, a bookbinder at St Joseph’s Home, Malta, at the time of De Piro’s administration, testified about the type of relationship the Director had with the employees at the Institute, “He used to pay his employees himself. He was always cautious to give some extra pay to those who needed it without letting anyone else know about this. He was a respectable man.”

During the first years of the 20thcentury it was very rare that anyone got any social benefit related to employment. It was only in 1920 that Dr Nerik Mizzi, a politician, presented a draft copy of a law about this in the Council of Government. His was “An Ordinance to make provision for the grant of compensation to workmen for injuries suffered in the course of employment”. At this same time there existed in Malta the Camera del Lavoro. Its primary aim was precisely the safeguarding of the interests of the workers in the following elections, according to the new Constitutions. This “Camera”, in April 1921, made an appeal for the establishment of the “Workers’ Party”. Those who responded positively to the appeal met on 15th May 1921. Their electoral programme included the unemployment, the payment of the employees and their working hours, a law about the compensation of injuries at work, old age pensions, etc. In the Legislative Assembly and in the Senate, the “due camere” of the Maltese Parliament, there was never a lack of interest about the legislation of social benefits. On 16th May 1927 Prime Minister Ugo Mifsud presented for the first time the “Widows and Orphans Pension Act”. It was read again on the 23rd of the same month. It was approved after the third reading at the end of May 1927. In spite of this lack of factual social assistance to those who were injured at work, Mgr Joseph De Piro helped financially an employee who was injured while doing his work at St Joseph’s, Malta. In the Income and Expenditure ledger the Servant of God wrote: “To … Nazzareno Attard for medical treatment of an ailment as a result of his work”.

From the pages which make up the file “Mgr Joseph De Piro : Instructions to Fr Joseph Spiteri”, it seems that at one time, for some reason or other, Director De Piro decided to entrust one of the priests of his Society, Fr Joseph Spiteri, with the payment of the employees at St Joseph’s, Malta. He therefore wrote down some instructions which could help Spiteri in the execution of his duty. Among these instructions there was mention of the pension of two employees, Sciberras, the carpenter, and the wife of … To the former Spiteri was instructed to give £1. 10. 00 and to the latter £0. 10.00, a month. Pension was also given to the wife of one of the workers who probably died while still at work, “Pension to Bianco’s widow; he was the shoemaker”.

1.2 Member of the National Assembly - justice with all the Maltese

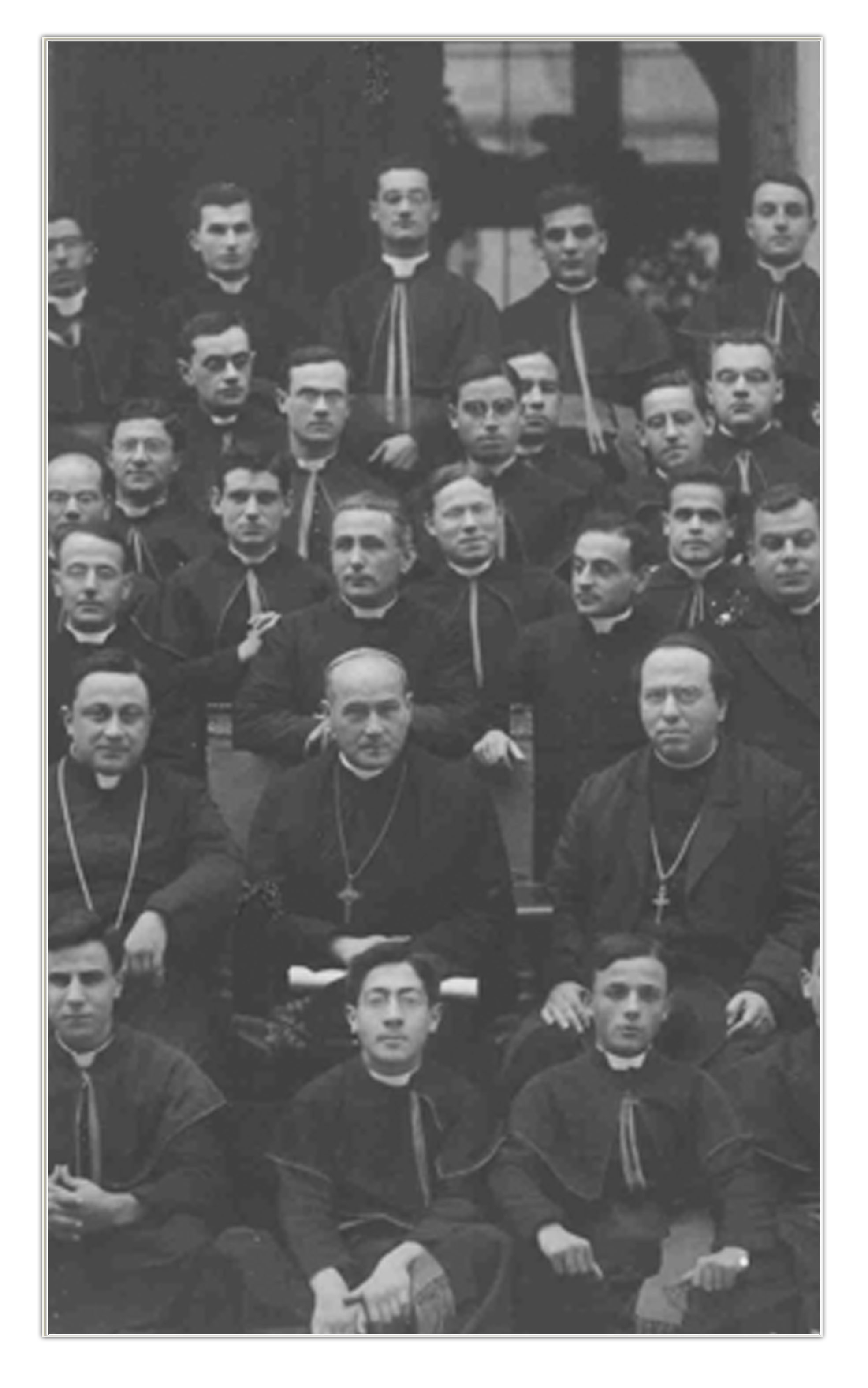

In 1918, Dr. Filippo Sceberras started a national movement for greater constitutional liberties in Malta. Associations in Malta and Gozo were invited to send delegates to a National Assembly. The 270 delegates were chosen from different walks of life. Mgr De Piro was nominated as one of the four representatives of the Cathedral Chapter and the clergy.

The National Assembly had its first meeting on 25th February 1919 and a proposal for a greater autonomy in local affairs was accepted. This proposal, which met with half-hearted enthusiasm by the British Colonial Authorities, served to raise expectations among the general Maltese population.

1.3 The Sette Giugno Riots

1.3.1 Saturday, 7 June1919 - justice with the unemployed and the other poor Maltese

The second meeting of the National Assembly was held on Saturday, 7th June 1919, at the Giovine Malta, Valletta and at a time when there was a considerable tension on the Island owing to the widespread unemployment. A fortuitous spark turned the mass of people who went to Valletta on that fateful day into a riotous mob. The Maltese policemen could not control them and the British soldiers who were called up in their stead lost their heads and fired on the unarmed rioters. Four Maltese men died from gunshot wounds that day, with a further two dying in the following days. All this took place while the National Assembly was discussing a proposal to select a Central Commission to draft a constitution for Malta. Mgr De Piro in his capacity of Dean of the Cathedral Chapter was chosen as the representative of the Island’s Cathedral Chapter and clergy among the fifteen representatives of the Central Commission.

The second meeting of the National Assembly was dramatically interrupted when the crowd brought one of the above mentioned wounded men into the Giovine Malta. Those who entered the hall asked the delegates to intervene on their behalf with the British Government. Out of the many members present for the second meeting only a few remained to give a hand: Advocate A. Caruana Gatto, Advocate S. Vella, Fr Nerik Dandria, Councillor G. Vassallo, Saviour Zammit Hammet … and Mgr Joseph De Piro. These ran the streets of Valletta, trying to calm down the mob. An Inquest Commission was set up by the Government in order to establish the facts of that sad event. This was made up of Judge A. Parnis LLD, as President; Dr M. Debono LLD; Magistrate L. Camilleri LLD; Col E.W.S. Broke CMG, DSO; and Lieut., Col., W. T. Bromfield. Mgr De Piro was called to give his testimony on 21st and 26th August 1919. Here are the facts as reported by him, and some of the others who accompanied him:

Judge A. Parnis told De Piro, “Your name has been mentioned by many witnesses. Can you, please, tell me what you saw on Saturday, 7th June and Sunday, 8th June?”

De Piro replied “I was present at the meeting of the National Assembly as Delegate of the Cathedral Chapter. After the discussion had lasted an hour and a half, someone entered the hall of the ‘Giovine Malta Club’ where the Assembly was holding the meeting. The person who came in showed us a handkerchief stained with blood and said: ‘See what they have done to us; you must protect us, you must protect us’. After this, order was restored and the meeting was closed. I was asked to find some other members of the Assembly so that we might try to restore peace among the people. I accepted the request. We were six or seven. We tried to find out by telephone where to locate Mr. Robertson, the Lieutenant Governor, and we were informed that he was in the office of the Commissioner of Police. We rang up the Assistant Commissioner of police to give us police protection, to accompany us to the police station; but no help was forthcoming.”

Mgr De Piro continued: “We went on our own and tried to enter the Law Courts by the back door in Strada Stretta. Then we could reach the police station, but we did not succeed. We tried again and from Strada Stretta we went on to Strada S. Giovanni, but as we reached Strada Reale we heard a shot. So we turned back to the Club, the ‘Giovine Malta’. Later we learnt that those were shots fired accidentally by soldiers in the Police Station.”

Major General Hunter Blair received the following information: “A telephone message from the Lieutenant Governor who was at the police station informed me that the Delegation wished to see me at my home. I said ‘I am prepared to receive them’. I later got another telephone message telling me the Delegation were on their way to me. However, the Delegates did not manage to make their way through the crowds, and so they turned back to the police station.”

Mgr De Piro continued, “In the Club, the ‘Giovine Malta’, we found the Assistant Commissioner of Police waiting for us, and he accompanied us to the police station.”

The Lt. Governor, Mr. Robertson, was at the Law Courts. So they went through Strada S. Lucia and Strada Reale to enter the Courts. Mgr De Piro omitted in his evidence what occurred there. Advocate Caruana Gatto relates: “The first time we tried to enter the Law Courts, people in the crowd were unfriendly towards us, especially towards Mgr De Piro, and shouted: ‘You are to blame for all this!’. Mgr De Piro replied: ‘Well, well. We are trying to save you, and you are blaming us!’ ”

At the end of his evidence, Monsignor was asked many questions. One of these was, “Did not someone swear at you?” Mgr De Piro answered all the questions, but according to Alexander Bonnici, the biographer, he gave no importance to the above. He did not want to harm his people, feeling that the impatient crowd was not inciting an attack on the clergy. Words, said in anger by persons in a frustrated crowd and addressed to him as a priest, were ignored and omitted in his evidence. However, later, on 9th June, there were evident signs of anti-clericalism in the angry mob. Mgr De Piro’s equanimity in his evidence again revealed his integrity.

Mgr De Piro continued: “We spoke to the Lt. Governor , asking him to withdraw troops from the streets, and we guaranteed that the people would be pacified. Robertson was not fully convinced, and several times he asked us the same question: ‘Were we really able to guarantee a peaceful outcome?’ We answered that it was necessary for us to obtain permission to address the crowd from one of the windows of the Law Courts. This was granted.... Advocate Caruana Gatto spoke to the crowd, relating what had passed between us and the Lt. Governor. He asked the people to disperse, thus helping us as mediators to keep our word to the Lt. Governor. The crowd showed signs of co-operation, and we thought we had succeeded in our task. This, however, was not yet to be. The crowd first insisted on the soldiers leaving the Law Courts. This request was passed on to Mr. Robertson, who promised to order all soldiers back to their barracks . . . The excited crowd demanded more than the departure of soldiers from the Law Courts and in loud voices they claimed that justice be meted out to them.”

In his evidence, Fr Enrico Dandria, one of the members of the Delegation, said, “We promised them that whoever had been guilty of the shedding of blood on that day would be punished.”

Gatto affirmed the same: “We spoke to the crowd and assured them that those responsible for mistakes made on that day would be punished. We advised the crowd to disperse. Mgr De Piro, Advocate Vella and myself felt they were satisfied and the crowd started to disperse, when unfortunately at that moment, a group of Royal Marines arrived, and the crowd was infuriated again.”

De Piro added that it took two and a half hours to calm down the crowd, because the Marines appeared to be heading towards the Law Courts. Whistling and booing became tumultuous and it was feared shooting would start again if the people lost their control. Fortunately this did not ensue. De Piro stated that the Delegation remained there until all the Marines had left the Law Courts.

This statement tallies with Fr Enrico Dandria’s evidence, “We went out and told the crowd to promise not to molest the Marines; and we told the Marines to take no notice of the whistling, while they were walking out of the Courts. They felt reassured by our words, and we accompanied them as far as St. John’s Church.”

1.3.2 Sunday, 8th June 1919 - justice with the unemployed and the other poor Maltese (continued)

The following day, 8th June, turned out to be a day full of turbulence and a time of grave anxiety for De Piro. The Maltese were still restless, and, as usually happens in times of riots, criminals take advantage of the situation for their own interests, and are not in the least concerned with love of country. In his evidence the Servant of God did not refer to his own efforts to move Advocate Caruana Gatto to continue their work of peace, but the words of Caruana Gatto reveal Monsignor as the leader of the mediators, “Sunday morning I was not feeling well. At 8.30, Mgr De Piro came and said: ‘Yesterday we assumed the responsibility of calming down the people. It is our duty to see what we can do to put a stop to this unrest. We must do something this very day’.”

Advocate Caruana Gatto was prepared to do his part. He felt it necessary to have the support of Mgr De Piro, because his presence made him feel strong enough to face the unruly mob. That same morning, serious incidents had taken place: an English soldier had been gravely injured, the printing office of the Malta Chronicle had been attacked and there had been abusive shouting in front of the Casino Maltese. Mgr De Piro stated: “On Sunday morning I went with Advocate Caruana Gatto and Advocate Serafino Vella to Dr. Sceberras in Floriana, who came back with us to Valletta and we decided to go to General Hunter Blair, who was the Officer Administering the Government. We wished to warn him that we were expecting trouble, as there was great unrest among the Maltese. A rumour was going round that a British soldier had been killed, and we wanted to stop the riot from getting out of control. I cannot remember exactly what we said to General Hunter Blair; I was very upset like the rest of us. The General addressed the crowd from the Palace balcony. The crowd clamoured for an inquest and the General promised to authorise it.”

The President of the Inquest asked De Piro if he had asked the General to speak to the people from the balcony of the Palace. De Piro answered: “It was the General himself who offered to speak. The crowd demanded that the troops would not be allowed to leave the Island before the Inquest would be held. The General promised he would see to that. We also spoke to the General who promised the Inquest would be held, and further promised that officers and persons involved in the happenings would not leave the Island until the Inquest be closed.”

From the evidence given, it was obvious how serious matters were. In the report at the conclusion of the Inquest, the cause of the riot was commented on, “Before the war, the number of workmen employed at the Dockyard had been around 4,600, and during the war it rose to about 12,000. It was understandable that the same number could not be retained. Discharges were expected, and the local employment market was insufficient for the number of unemployed.”

Mgr De Piro defended the cause of the Maltese, and in his evidence he added: “I spoke to the General regarding the discharges from the Dockyard because the people were affirming that about 2,000 workmen had been discharged, and I personally felt this was unfair to the Maltese, who had done four years of valid work during the war. The General replied that my statement was not correct; only 500 had been discharged.”

Sunday afternoon brought with it still more turbulence, and Lt. Governor Robertson was again in touch with the mediators, asking them for help. Here Advocate Caruana Gatto said: “On Sunday afternoon, I received a message from Mr. Robertson, sent by the Inspector of Police, saying he wished to see me. I went to the Police Office in the Law Courts building and met Mr. Robertson, who told me he wished me to be with him when he spoke to the people because he knew the crowds were still very agitated. I told him that my presence alone would be useless, and I had to have with me Mgr De Piro and Advocate Serafino Vella. It was necessary for the people to see the same faces they had seen before.”

When Advocate Caruana Gatto went to ‘La Valletta Band Club’, he found greater unrest: firing had taken place and the Maltese were being pelted with pennies. Advocate Caruana Gatto met Advocate Vella, and together they went to Robertson, who was at the General’s house. Mgr De Piro entered and gave them the news that the crowd was becoming uncontrollable, and that Francia’s home, facing the Royal Theatre, was being attacked. Mgr De Piro said, “We must go and tell the people to stop this aggressive rampage; it will only delay and ruin our good cause.”

The Servant of God minimised his share in the ‘cause’ when he related what happened, “I was asked to join Advocate Caruana Gatto and Advocate Serafino Vella for the same reason: to calm down the people. I accepted, and together we went close to the area of the Theatre.”

Here Monsignor omitted what he had witnessed. Advocate Caruana Gatto said, “Mgr De Piro, Advocate Vella and I were standing on the portico of the Theatre, and from there we assisted at the assault on Francia’s house. People with wooden rods in their hands were trying to break down the front door of the house.”

Advocate Caruana Gatto made here a relevant comment, “I must say that on that day, the crowd was not made up of the same people as the day before. I saw many faces familiar to me in the Criminal Court.”

The President of the Inquest Commission asked Mgr De Piro if he had spoken to the people that afternoon. The Servant of God answered, “No; only Advocate Caruana Gatto tried to speak and later when his voice was not audible because of the deafening noise, and he was inclined to leave the spot, I was asked to tell the people to come closer to us to be able to hear us.”

The President of the Inquest Commission asked again De Piro, “Did you not tell them that what they were doing was wrong?” De Piro answered, “I wished to say something, but all I said was for them to come closer.”

At this point a nasty incident occurred, of which we have first-hand evidence from Advocate Caruana Gatto. It appears Monsignor preferred to keep silent about what happened: “At first the mob abandoned the attempt on Francia’s house, and gathered around us. I told them that attacking that house had nothing to do with politics, and asked them to stop if they wanted our political demands to have a successful outcome. However, the criminal element in the crowd gained the upper hand. They started booing us, swearing and stealing money from our pockets, and returned to Francia’s home to break down the back door. We warned them that if they carried on in this way, the army would be called in again, and there would be bloodshed. Our words, however, had no effect.”

Mgr De Piro did not want to refer to this pillage and said simply, “We realised all we were doing was of no avail; the two gentlemen with me (Caruana Gatto and Vella) decided to leave the site, and I went with them.”

Advocate Caruana Gatto was taken ill and retired to bed.

Although the members of the National Assembly involved in the mediation between the Government and the Maltese were six people, only three were continually following the events and placing themselves in danger: Mgr De Piro and the two lawyers, Caruana Gatto and Serafino Vella.

This was not the only task assumed by Mgr De Piro. For that very day, 8 June, a Committee was formed ‘Pro Maltesi Morti e Feriti per la Causa Nazionale il 7 Giugno del 1919’. De Piro was the only priest member of this Committee, which continued meeting until January 1926, offering help to the families of the victims and to those who had been injured. He was in fact the treasurer of this Committee.

1.3.3 Monday, 9 June 1919 - justice with the Archbishop

On Monday, 9th June, the third day of the riots, Mgr De Piro struggled to make justice with Archbishop Mauro Caruana. His Excellency was being suspected that he was siding with the British Government. In fact at one moment some of the rioters even attacked the Archbishop’s palace in Valletta. The Servant of God was inside the palace at that moment. He together with Bishop Angelo Portelli, the Apostolic Administrator, went out of the palace and addressed the angry mob: “What do you want, my sons?” Some were heard saying, “We want to burn down the Curia!” The Servant of God answered, “All that there is here, isn’t it yours? Come. .. Calm down. .. And now quietly move away”.

The kind tone and approach of Bishop Portelli and Mgr De Piro, two people who had done so much for the Maltese brought about a certain lull in the anger of the crowd.

Fr Tony Scibberas mssp

ASP Web Pro Website designed & maintained by MSSP| Disclaimer | Copyright | Privacy Policy | Sitemap |

© 2006 Missionary Society of Saint Paul, MSSP